By : Jan Keulen

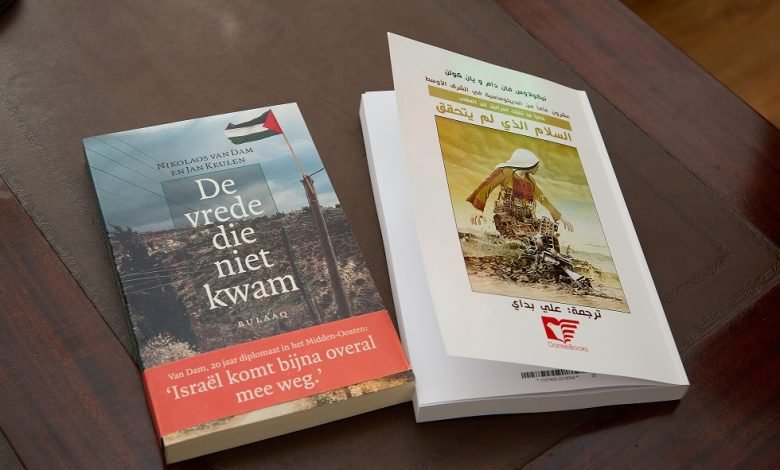

Jordan Daily – Recently, Daree Books Canada published ‘The Peace That Never Came’ in Arabic. Journalist Jan Keulen and diplomat Nikolaos ‘Koos’ van Dam were surprised that after almost three decades there would be still interest in this book, originally written in Dutch.

Our book was published in 1998, the year that the state of Israel celebrated its fiftieth anniversary. But among the anniversary books published at the time, ‘The Peace That Never Came’ stood out for not being very complimentary of Israel. On the book’s cover was Van Dam’s quote, ‘Israel gets away with almost everything’.

I met Nikolaos ‘Koos’ van Dam in Beirut in 1980. He was the first secretary of the Dutch embassy, and I was a correspondent for the Dutch newspaper Volkskrant. Our country was very interested in Lebanon at that time. In particular, Israel’s attempts to eliminate the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) in Lebanon were closely followed. On the Lebanese side of the border with Israel, eight hundred Dutch soldiers were stationed as part of the UN peacekeeping force UNIFIL.

Koos and I experienced some of the most dramatic episodes of the war in Lebanon: the Israeli invasion and Sharon’s advance to Beirut, the months-long siege of the western half of the city and the massacre in the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Chatila. In our book we wrote about the brutal actions of the Israeli army, the war crimes and the fog of war: how the harsh reality is hidden from view by misty and obfuscating terminology. Hence the red ribbon with the text ‘Israel gets away with almost everything’.

It has now been almost three decades since ‘The Peace That Did Not Come’ was conceived. In 1998, I spent a week with Koos in Ankara, where he was ambassador. The interview that lasted for several days served as raw material for the book, which was set in two distinctive fonts: one representing Van Dam’s voice and the other my own observations. In this way, ‘The Peace That Did Not Come’ became the result of an intensive exchange of ideas between the diplomat and the journalist, who each tried to understand and explain the Middle East from their specific field of work.

My journalistic work in Beirut in the eighties had completely turned into war correspondence. My hope was that ten years later, from the Jordanian capital of Amman, I would be able to report on a budding peace. In 1993, the Oslo Accords had been concluded between Israel and the PLO. A year later, Israel and Jordan made peace. A new era had dawned. Or so we thought.

During that period, I was intensively involved in what was euphemistically called in journalistic parlance ‘the peace process’. As a correspondent for de Volkskrant, I frequently crossed the Allenby Bridge to report on the Palestinian side of the equation. However, developments in East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza became less hopeful by the day. The Israeli occupation deepened. 1998 in particular, the last year of my correspondentship, was a year of disappointment and disillusionment. The title of our book, ‘The Peace That Never Came’, refers to this.

The assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Rabin in 1995 and the election of Benjamin Netanyahu in 1996 increased the sense of tension and uncertainty in the region. Netanyahu, who had been a fierce opponent of ‘Oslo’ from the outset, refused even to discuss the status of East Jerusalem, the return of Palestinian refugees and the issue of settlements. At the same time, everywhere in the occupied territories, I increasingly saw the red roofs of the expanding settlements. ‘Trucks are driving back and forth with construction materials, bulldozers are working to build new bypass roads and concrete mixers are running at full speed,’ I write in ‘The Peace That Never Came’. ‘The feverish construction activities seem to be aimed at creating more faits accomplis and are irreversibly changing the situation on the ground.’

It was clear to us in 1998: Israel does not want a two-state solution at all. Does Israel actually care for peace, or does it want nothing more and nothing less than the whole of Palestine, from the Mediterranean Sea to the Jordan River? More than a quarter of a century later, we must answer that question with a resounding yes: of course, Netanyahu’s Israel wants the whole country, and preferably with as few Palestinians as possible. The international community’s proposal to exchange ‘land for peace’, the basis of the peace process, had become nothing more than an empty incantation.

In our book, Koos van Dam pointed out the weak negotiating position of the Palestinians. ‘The Israelis hold all the cards. The West Bank is completely fragmented, with a number of autonomous Palestinian enclaves with roads around them to Jewish settlements. After Palestinian attacks or protests, Israel imposes collective punishments that affect the entire population. Workers from Gaza are no longer allowed to work in Israel, the semi-autonomous Palestinian areas on the West Bank are further closed off.’

It has been almost three decades since we wrote this, but it sounds familiar…

The Second Intifada was supposed to break out two years after the publication of our book, but we clearly saw the storm coming. ‘If the Palestinians lose confidence in the peace process, there is a chance of a new intifada, of more violence out of frustration and despair.’ Koos added: ‘But what is the alternative to continuing to talk? ‘ We are now seeing that alternative in practice. Since 2014, there has been no more talking. The peace process is dead, the colonization of Palestinian territory continues unabated, and if there is any talk at all, it is through weapons.

In the first quarter of the 21st century, we saw the attacks of September 11, 2001, the American invasion of Iraq, the Arab Spring and civil wars in Iraq, Yemen, Syria, Sudan, and Libya. Bookcases were filled with books about the never-ending Israel-Palestine issue. The Middle East has undergone dramatic changes since we wrote ‘The Peace That Did Not Come’. Except that, indeed, peace was still far away in Israel/Palestine.

I was therefore surprised when I heard that our book, after all these years, had been translated into Arabic. Ali Badai, an Iraqi engineer living in the Netherlands, took the initiative to translate our book after discovering it by chance. Badai was used to the one-sided, pro-Israeli image that the Dutch media usually paint of the Middle East.

This book painted a completely different vision. He also found the analysis of Dutch diplomacy and journalism regarding Israel/Palestine important for an Arabic-speaking audience to understand European thinking. The Arabic version of our book has now been published by a publisher in Ontario, Canada. A publisher in Iraq will also publish the translated book shortly, with three added recent articles by Koos van Dam.